Tips for Time Lords

From Code For Your Life

Work deeply. Don’t waste time on things that don’t matter.

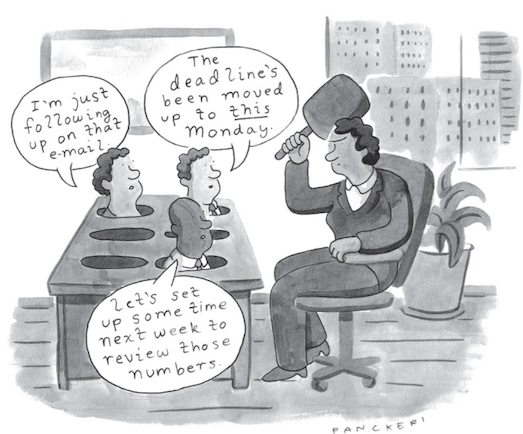

The First Law of Time is:

If you don’t take control of your time, someone else will.

You’ve probably heard of the “big rocks first” strategy, popularised by Stephen Covey. The idea is that you’re trying to fill a jar with rocks, pebbles, and sand (not sure why you’d need to do this, but never mind). If you put the sand and pebbles in first, you’ll find there’s no room for the big rocks. In other words, if you’re going to get the big rocks in there, you need to put them in first, and let other things fill up the spaces around them.

Your day is the jar. The things you really want to do are the big rocks. The stuff that comes at you, unasked and often unwanted, is the sand. If you wait until the jar is almost full of sand, it’s hardly surprising that most days you won’t be able to fit in a single rock.

What can you do?

Make a plan

For each hour of the working day, write down what you plan to be doing during that hour.

Some of these hours will already be filled up; perhaps you have meetings, lectures, dates, or other appointments that represent commitments to other people, or even yourself. But there will also be blank spaces.

Congratulations: you’ve just won your first small victory for time management. Thinking about your time in advance is the first step to using it wisely. Now you have the relative luxury of deciding what to do with those blank spaces.

Make time for what really matters

No doubt you have a number of commitments to meet, which will use up some of that time. And some of it should be reserved for yourself, to rest, to regroup, to breathe, to go for a walk, to sit quietly with a cup of coffee, to read a book, watch the birds, or to spend quality time with those you love. In other words, to live.

The aim of managing our time more effectively is not so that we can cram more work into it. There’s no point merely running faster on the hamster wheel of death. Instead, let’s make sure we’re spending time on what really matters: that is, the things we’ll wish we’d done more of when, as they inevitably will, our days come to an end. Today is a gift, as the saying goes; that’s why they call it the present.

Things to do: make a list

If you’ve ever been hiking in difficult terrain, you’ll know that it requires two quite separate skills: vision and focus. Vision, because you need to be able to scan the landscape at long range to see where you’re heading. Focus, because you need to look where you’re putting your feet.

You can’t exercise both vision and focus at the same time, so you need to alternate. First look ahead at the landscape, then down at your feet, and so on.

The same applies to your to-do list. Some people say they don’t believe in to-do lists, but the fact is that everybody has one. Whether or not you like the idea, you have a bunch of things to do. Some people just keep the list of those things in their head, that’s all.

And that’s a terrible place to keep it. Your brain is a marvellous organ, but it’s not designed for retaining lists of arbitrary items and prompting you about each of them at the right time, in the right place, in the right way.

Do you have a flashlight somewhere with dead batteries in it? When does your mind tend to remind you that you need new batteries? When you notice the dead ones! That’s not very smart.

If your mind had any innate intelligence, it would remind you about those dead batteries only when you passed live ones in a store. And ones of the right size, to boot.

—David Allen, “Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity”

Get everything out of your head

Instead of cluttering up your brain with dumb things like “buy batteries”, give it a good clear-out so that it can really start working. Grab a piece of paper, or a text file, and start jotting down all the things that you know you need to do or remember.

At first this will be easy, then hard, then easy again. What I mean is, there are probably four or five things buzzing angrily around your brain right now like trapped bees, making you anxious in case you forget them. These will come straight away.

Once you’ve freed those bees, it may seem like there’s not a whole lot else you need to remember. But just sit for a minute and let your mind spin gently in neutral. One or two more things will pop into your consciousness; write them down. As one thing occurs to you, it may trigger a few more. Keep going with this process until you really can’t think of anything else.

You will probably find you’ve covered one or two sheets of paper with things—perhaps an alarming number of things. More than you could reasonably do in the next month, even if you spent every minute of every day on them. Some of them will be quick and immediate (“buy batteries”), others more vague and ill-defined (“learn time management”), and some long-term and strategic (“have fulfilling career”).

That’s okay. It’s not a problem. While it may be a shock to see so much stuff written down, the truth is that your to-do list hasn’t changed. It’s just that you’re seeing it for the first time. Up to now, all this stuff has been buzzing round your head, cluttering it up and blocking more interesting or valuable thoughts. And, whether you know it or not, it’s also been stressing you out.

Deep work

Many people believe that they can multi-task, but the truth is that’s just not something the human brain is good at. If you think you’re multi-tasking, you’re probably just half-assing a bunch of things at once, instead of really doing any of them. Half-watching something on TV while half-reading something on your phone; half-listening to someone on a Zoom call while half-thinking about how to fix your code.

If you have a normal-sized brain, then half of it, or even less, won’t be enough to do good work on any particular task. And what’s the point of doing bad work? Better to skip that task altogether, and focus on something else.

Schedule deep work deliberately

There’s a popular myth that we only use 10% of our brains. It feels true to us because we’re perfectly well aware that we tend to use our brains in an inefficient and unfocused way.

The truth is simply that your brain is a lot more powerful than you realise. You just haven’t really given it a chance to show what it can do. And that means dropping the attempts to multi-task. Instead, focus on just one thing for a short period, and do it really well.

This is exactly what you’re going to do in your day planning. You’re going to start by planning sessions of deep work: that is, using your brain at full power to achieve something, free of distractions, interruptions, and irrelevant activities.

Remove all distractions

At first it feels scary to put your phone on “do not disturb” and quit Slack and email. What if you get an urgent message? Well, what if you do? You can’t spend your whole life on pause, waiting, just in case someone needs you. And it’s usually possible to configure these things so that the people you really care about—your child, spouse, partner, parent—can reach you in an emergency, even when others are temporarily blocked.

The next step to deep work is mental attitude: preparing yourself to focus and work without procrastination. Like yoga or jogging, this is always hardest on the first day. You may need to move some toys out of reach; if you tend to use the internet to give yourself a quick break whenever you feel bored or stuck, use a browser extension to block access to your favourite time-wasting sites.

You can still take screen breaks during a deep work session, and that’s a good idea, but don’t just switch from your monitor to your phone or tablet. Go and stand outside for a few minutes and listen to the birdsong, or (depending where you live) the traffic.

Don’t overdo it

How long should you schedule for deep work sessions? This depends on you, but it’s wise to start small. If you’re not used to working deeply, block out half an hour to an hour to begin with. That’s enough time to achieve a surprising amount, if you’re really focused.

However, when you feel yourself starting to flag, don’t push it. Listen to the signals from your brain and body telling you that you’ve done enough for now. If you’re really flying, the temptation is always to push on a little more: add one more feature, one more chapter.

Instead, make an intentional decision to stop before you start feeling tired and burned out. When you’re making scrambled eggs, if you wait until they look done, they’ll actually be overdone. The same applies to your brain. Learn to take it off the heat just before it turns into an unappetising, rubbery mess.

You should also time the end of the session so that you have a reasonable gap before the next appointment. Don’t try to jump straight into something else. After a session of deep work, you’ll need a break, and for once you’ll have really earned it.

Not all work is deep work

Depending on your job, you may need to spend a greater or lesser amount of your day just doing things like triaging bugs and emails, responding to chat messages, making phone calls, and so on.

This “shallow work” can be important, too. But it doesn’t take much concentration, and it can be done in short time slots, whenever you have a few minutes. When you know in advance that you won’t be able to get long, uninterrupted blocks of time for deep work, use the time you do have to crank through your shallow work queue.

A certain amount of shallow work is part of everyone’s job. What’s going to make the difference between you and the next person is your ability to do deep work.

Some people never do deep work at all. It should be relatively easy to outperform them. Then you can concentrate on outperforming the people who are also doing deep work, but just aren’t as good at it as you are.

Your ability to do this work is completely dependent on the prevailing interrupt rate. If each interrupt robs you of fifteen minutes of flow, and you get interrupts every fifteen minutes, then you should expect to achieve absolutely nothing of value.

Sadly, that’s the case for many people. To avoid this, reduce or eliminate interrupts.

Make yourself uninterruptable

Should we simply hope that people will realise we’re busy and not interrupt us? Good luck. A better idea is to take control of your interruptability, and set boundaries for access to your attention.

That’s actually something you’re allowed to do. Everyone does not have the right to interrupt you and claim your attention.

The first line of defence against these interruptions and attempts to claim your attention is, as we’ve seen, to make yourself physically uninterruptable by turning off the various communication channels through which the attacks will come: Slack, Teams, phone, email, and so on. Not forever; just for an hour or two during your scheduled deep work session.

If you’ve inadvertently trained your co-workers to expect instant access to you at every hour of day or night, and you probably have, it may surprise them at first to find that you’ve gone dark.

Where this is the case, have a conversation with them about it and explain what you’re trying to do. The odds are, they’ll be fine with it once they know what’s going on.

People will usually respect your right to become inaccessible if these periods are well defined and well advertised, and outside these stretches, you’re once again easy to find.

—Cal Newport, “Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World”

Attention is a muscle: flex it

Your ability to do deep work is critically dependent on your ability to sustain your attention for long periods. Unfortunately, almost everything in modern society seems designed to shorten and weaken our attention spans: tweets, TikTok videos, even text messages.

If you never use your muscles, they’ll get weaker. If you never have to sustain your attention, it will get weaker. If you find, whenever you try to do some cognitive work such as writing or coding, that your concentration fades after a few minutes and you start craving breaks and distractions, then you know what I mean.

But the good news is that even weak muscles can get stronger, if you train them. You can train your attention by using it. Read long books; spend some time in quiet meditation; watch a whole movie from start to finish without checking your phone. This will be very difficult at first, but you can start small and build up to more challenging attention workouts over time.

Quit social media. That sounds blunt, but it’s an essential step if you want to become better at using your brain for a living. Social media is not only a waste of your time—it’s just a great babble of other people’s worthless opinions—but it positively harms your ability to concentrate, too.

It’s also extremely habit-forming, and that’s not a coincidence. Social media companies maximise their profits (or minimise their losses) by using every trick in the book to grab and hold your attention. They are mining you for your attention, and this ruthless extraction has roughly the same effect on your brain as strip-mining has on the landscape.

Time is a non-renewable resource

As you get a little older, and a little further along in your career, you’ll realise more and more that time is the one thing you’ll never have enough of, and once it’s gone, you can’t get it back.

This knowledge could stress you out, making you feel as though you have to wring the maximum utility out of every minute. But living like that is no fun: who wants to race to the grave?

If you take control of your schedule, declutter your head, do deep work, manage interrupts, and build your powers of sustained attention, you’ll claw back an awful lot of time that would otherwise have slipped away. What should you do with it?

My suggestion: invest it wisely, in thinking, laughing, loving, and living. Don’t waste another minute of it on things that don’t matter. You’ll never look back on your life and wish you’d attended more meetings, or spent more time on Twitter.